British Revolutionary War Leaders |

Colonial Wars |

American Wars |

Link To This Page — Contact Us —

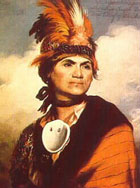

Indian Chief Joseph Brant (British Ally)

|

| NAME |

| Brant, Joseph |

| BORN |

| c. 1742 Ohio River Banks |

| DIED |

| 24 November 1807 Burlington, Ontario, Canada |

| ARMY |

| British Ally |

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (c. 1742 – 24 November 1807) was a Mohawk leader and British military officer during the American Revolution. Brant was perhaps the most well-known North American Indian of his generation. He met many of the most significant people of the age, including George Washington and King George III. The American folk image emphasized the atrocities his forces committed against settlers on the western frontier.

Brant was born at Cuyahoga Ohio Country on the banks of the Cuyahoga River, near present-day Akron, Ohio, during the hunting season when Mohawks travelled to the area. He was named Thayendanegea, which can mean two wagers (sticks) bound together for strength, or possibly "he who places two bets." Dr. David Faux's study of the Fort Hunter Church records indicates that his father's name may have been Peter Tehonwaghkwangearahkwa, who would have died before 1753. Other sources cite the father's name as Nickus Kanagaradankwa. His mother Margaret, or Owandah, the niece of Tiaogeara, a Caughnawaga sachem, took Joseph and his older sister Mary (known as Molly) to Canajoharie, on the Mohawk River in east-central New York, where she had lived before her family moved to the Ohio River. His mother remarried on 9 September 1753 in Fort Hunter (Church of England) a widower named Brant Canagaraduncka, who was a sachem of the tribe. Her new husband's grandfather was Sagayendwarahton, or "Old Smoke," who visited England in 1710. While this bettered his mother's fortunes, it conferred little status on her children, as Mohawk titles descended through the female line. However, Brant's stepfather was also a friend of William Johnson, who was to become General Sir William Johnson, Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs. Johnson married Joseph’s sister, Molly, and arranged for Joseph to be educated at Eleazar Wheelock's Moor's Indian Charity School in Connecticut, the forerunner of Dartmouth College, where he studied under the guidance of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock. When he returned to his people, he became a translator for a local missionary.

Starting at about age 15, Brant took part in a number of French and Indian War expeditions, including James Abercrombie’s 1758 invasion of Canada via Lake George, William Johnson's 1759 expedition against Fort Niagara, and Jeffery Amherst's 1760 siege of Montreal via the St. Lawrence River. He also acted as an interpreter for an Anglican missionary named John Stuart, with whom he translated the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language. He became a lifelong Anglican, and would build the first Protestant church in Canada, St. Paul's, Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks, which is now one of twelve Royal Chapels supported by the Crown throughout the world.

In 1775, he was appointed as Guy Johnson's departmental secretary for Indian affairs with the rank of Captain. Brant had previously been a translator for the department for some time. Soon after the fighting in the American Revolution began, Brant traveled to London with the new British Superintendent for Northern Indian affairs, Guy Johnson. Brant hoped to get the Crown to address past Mohawk land grievances, and the king agreed to give the Iroquois people land in Canada if he and four other Iroquois nations were to battle along with him.In London, Brant became a celebrity, and was interviewed for publication by James Boswell. He also became a Mason, and received his apron personally from George III.

Brant returned to North America in July 1776 and immediately became involved with Howe's forces as they prepared to retake New York. Although the details of his service that summer and fall were not officially recorded, Kelsay (pp. 182-184) has deduced that he was with Clinton, Cornwallis, and Percy in the flanking movement at Jamaica Pass in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776. It was at this time that he embarked on a lifelong relationship with Lord Percy, later Duke of Northumberland, the only lasting friendship he shared with a white man.

In November, Brant left New York City traveling northwest through American held territory. Traveling at night and sleeping during the day, he reached Onoquaga in early December and Fort Niagara by the end of the month. He urged the Iroquois to abandon neutrality and to enter the war on the side of the British. The Iroquois initially balked at Brant's plans partly because they considered Brant a minor war chief from a relatively weak people, the Mohawks. In August 1777, Brant played a major role at the Battle of Oriskany in support of a major offensive led by General John Burgoyne. Brant was not the ranking Iroquois war leader, as was sometimes represented, but after the failure of Burgoyne's campaign, Brant raised and commanded a combined force of about 300 Indians and 100 white Loyalists. He led them in a series of raids on American settlements in New York and Pennsylvania in 1777-1778. He led many other battles, either as leader of his Indian forces, or Brant's Volunteers, or together with British regulars, Butler's Rangers, or other Loyalist forces. In September 1778, he along with Captain William Caldwell led a mixed force of Indians and Loyalists in a raid on German Flatts. On November 11, 1778 he lead the attack in the Cherry Valley massacre. In 1779, Lord Germain promoted Brant to Colonel, but Frederick Haldimand did not pass this promotion along to Brant. In July 1779, Brant defeated a rebel force at the Battle of Minisink. When George Washington sent an army to reconquer New York in 1779, Brant was defeated by General John Sullivan on August 29, 1779 in the Battle of Newtown, as the Americans swept away all Indian resistance in New York, burned their villages, and forced the Iroquois to fall back to Fort Niagara. He wintering at Niagara in 1779-80. In 1780 he took part in a raid on the Mohawk Valley, where he was wounded in the heel at Battle of Klock's Field. Brant was sent west to Detroit to help defend against an expedition into the Ohio Country to be led by the Virginian George Rogers Clark. In August 1781, Brant completely defeated a detachment of Clark's army, ending the threat to Detroit. From 1781 to 1782, Brant tried to keep the disaffected western tribes loyal to the Crown in the aftermath of the British surrender at Yorktown.

In negotiating the Paris peace treaty that ended the war, Britain and the United States ignored the sovereignty of the Indians, and sovereign Six Nation lands were agreed to be part of the United States.

Brant became infamous for the Wyoming Valley massacre, which it was widely believed he led, although he was not present at the battle. During the war, he was known as the Monster Brant and stories of his massacres and atrocities created a hatred of Indians that soured relations for 50 years. In later years historians have argued that he actually had been a force for restraint in the violence that characterized many of the actions in which he was involved; they have discovered times when he displayed his compassion and humanity, especially towards women, children, and non-combatants. As an example, Lt. Col. William Stacy of the Continental Army was the highest ranking officer captured during the Cherry Valley massacre. Several accounts indicate that during the fighting, or shortly thereafter, Col. Stacy was stripped naked, tied to a stake, and was about to be tortured and killed, but was spared by Joseph Brant. William Stacy, like Joseph Brant, was a Freemason. It is reported that Stacy made an appeal as one Freemason to another, and Brant saved his life.

At Brant's urging, British General Sir Frederick Haldimand made a grant of land for a Mohawk reserve on the Grand River in Ontario in 1784. (Haldimand Proclamation, see also Six Nations of the Grand River). For the next twenty years, Brant would act as a tireless negotiator for the Six Nations, playing on British fears of Indian alliances with the Americans and/or the French, to preserve the Grand River land from encroachment by whites in and out of the Canadian government. His conflicts with British administrators in Canada regarding tribal land claims were only exacerbated by his relations with American leaders after the War. He was invited to Philadelphia by George Washington and Henry Knox in 1792 and 1797.

After the American Revolution, Brant also worked to bring about a confederation of the Six Nations with the tribes of the western United States, in order to resist U.S. expansion into the Northwest Territory. His attempt to create pan-tribal unity proved unsuccessful, though his efforts would be taken up a generation later by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. When the resistance in the Northwest became full-scale warfare (the Northwest Indian War), Brant was asked to negotiate a settlement by the administration of U.S. President George Washington. Brant was unable to arrange a truce, and the war continued, ending with the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

Although a War Chief, Brant was not an hereditary Mohawk sachem. However, his natural ability, his early education, and the connections he was able to form made him one of the great leaders of his people and of his time. His lifelong mission was to help the Indian to survive the transition from one culture to another, transcending the political, social and economic challenges of one the most volatile, dynamic periods of American history. A summing up of his life cannot be described in terms of success or failure, although he had known both. More than anything, Brant's life was marked by frustration and struggle. In his various roles as a youthful warrior, student, farmer, husband and father, British army officer, and Anglican convert and New Testament translator, he was totally committed. In his later years, as a politician-diplomat-negotiator, the frustrations were constant.

During his lifetime, Brant was the subject of many portrait artists. Two in particular signify his place in American, Canadian, and British history. George Romney's portrait, painted during the first trip to England in 1775-1776, hangs in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. The Charles Willson Peale portrait was painted during his visit to Philadelphia in 1797, and hangs in Independence Hall.

Joseph Brant was married three times, the first to Christine on 25 July 1765, and had two children, Isaac and Christine. His wife Christine died probably in the March of 1771 of consumption. His second wife, Susanna (Christine's half-sister) also died of consumption shortly after the marriage in 1773 without issue. In 1780, he married Catherine Adonwentishon Croghan, the daughter of the prominent American colonist, Indian agent, fur trader, and New York-Pennsylvania-Ohio landowner/speculator George Croghan and a Mohawk mother, Catharine Tekarihoga. They had seven children: Joseph, Jacob, John, Margaret, Catherine, Mary and Elizabeth. Through her mother, Catharine Adonwentishon was head of the Turtle clan, the first in rank in the Mohawk Nation. Her birthright was to name the Tekarihoga, the principal sachem of the Mohawk nation. She named her brother, Henry; through Henry and Catharine, Joseph was able to wield considerable power. After Joseph and Henry's deaths, she then named her youngest son John, who died unmarried. Elizabeth, a daughter of his 3rd marriage, was married to William Johnson Kerr, grandson of Sir William Johnson and Molly Brant, and their child subsequently became Chief. United Empire Loyalists, Thayendanegea's surviving sons, Joseph, Jacob, and John fought in the War of 1812.

Joseph Brant died in his house at the head of Lake Ontario (site of what would become the city of Burlington, Ontario) on November 24, 1807. His last words, spoken to his adopted nephew John Norton, reflect his life-long commitment to his people: "Have pity on the poor Indians. If you have any influence with the great, endeavour to use it for their good." The house was owned by descendants until the late 19th century, and is now the Joseph Brant Museum. In 1850, his remains were carried 34 miles (55 km) in relays on the shoulders of young men of Grand River to a tomb at Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford.